RELG 402 - World's Living Religions

Chinese Traditional Religion

Click on the pictures to see larger photos.

Chinese traditional religion has its roots in prehistoric China. One of the earliest beliefs was that the Universe (Heaven, earth, humanity, deities, nature) is made up of the same essential substance, called qi or ch'i.

Qi is manifested as two complementary forces, yin and yang, which represent the balance of nature.

Yin originally meant the shady side of a hill, but has come to represent the feminine principle, dark, moist, inert, cold, soft, something broken. Yin energy was at a maximum during the winter solstice each year.

Yang originally meant the sunny side of a hill, but has come to represent the masculine principle, bright, dry, active, warm, hard, something unbroken. Yang energy was at it lowest during the winter solstice, then began to increase, bringing growth and light through the year until it reached its highest level at the summer solstice.

Everything is composed of varying proportions of yin and yang.

Everything is composed of varying proportions of yin and yang.

The yin-yang symbol is often found in association with the "eight trigrams" used in divination. The trigrams are each drawn as three lines which may be broken or unbroken. The various combinations of broken and unbroken lines give eight possible combinations, and these are used in pairs in all possible combinations to give a total of 64 hexagrams. The hexagrams are thought to represent all possible situations in the universe, and are used in divination to discern the situation and give a judgment as to correct action.

The Confucian "Book of Changes", the I Ching, is used as a manual for the use of the trigrams in divination.

In addition to the yin-yang balance of the cosmos, Chinese traditional religion also regarded five as a special number, and referred to a cycle of "Five Phases" or vital forces. Other examples of groups of five are the "Five Directions" (north, south, east, west, center), the

"Five Sacred Mountains", the

"Five Planets" (Jupiter, Mars, Saturn, Venus, Mercury), the

"Five Colors" (blue, red, yellow, white, black), and the

"Five Poisons" (centipede, snake, scorpion, toad, lizard).

In the "Double Fifth Festival" on the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese year these groups of five play a prominent part.

The Five Phases are represented by the essences of Fire, Water, Metal, Earth, Wood.

Fire and Wood are thought of as reflecting yang, Metal and Water reflect yin, and Earth is neutral.

Everything in the cosmos is linked to an ongoing series of cycles of the phases.

In the first cycle, each phase gives rise to the next phase, and the sequence runs "Wood - Fire - Earth - Metal - Water"

In the second cycle, each phase destroys the phase which was before, and the sequence runs "Fire - Water - Earth - Wood - Metal"

Everything in the cosmos is linked to the cycles of the Five Phases, and also contains various proportions of yin and yang.

The purpose of the Chinese religions is to express the harmony of the cosmos, and to assist people to come into full harmony with the cosmos.

In the earliest stages of religion in China, before Confucianism and Taoism developed, there was an awareness of the spirit world, and the concept of a "High God", Shang Di.

During this period various "culture heroes" made innovations began to bring China out of the neolithic age. Some of these heroes are revered as divine beings in Chinese folk religion.

Fu Xi (ca. 2652 BC), the Ox-tamer, is credited with domesticating animals and with inventing nets for catching animals and fish, and also inventing marriage and thus instituting the family. He is also credited with inventing divination and the eight trigrams.

Shen Nong (ca. 2737 BC), the Divine Farmer, is credited with inventing the hoe and the plough, and with teaching the art of agriculture to the people.

Huang Di (ca. 2697 BC), the Yellow Emperor, invented warfare, and drove the "barbarians" out of what became the homeland of the Chinese Empire. His wife is credited with inventing silk culture.

During the Shang dynasty (1766-1050 BC) Chinese religion was characterized by worship of Shang Di (the Lord most High) and by divination and ancestor worship.

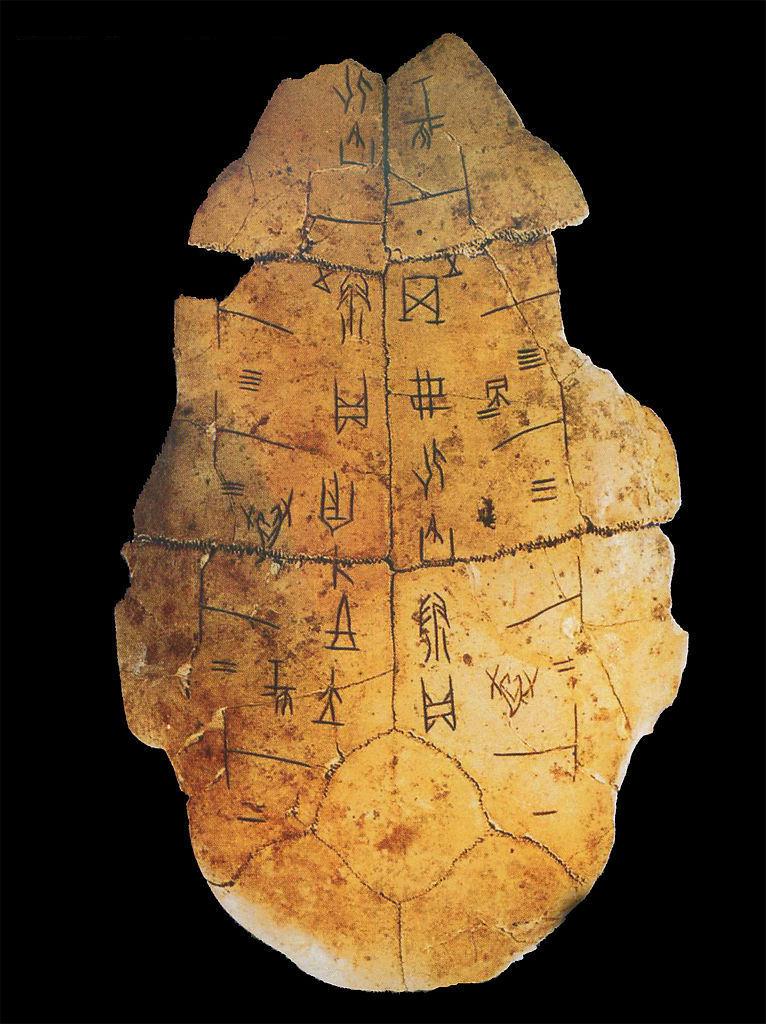

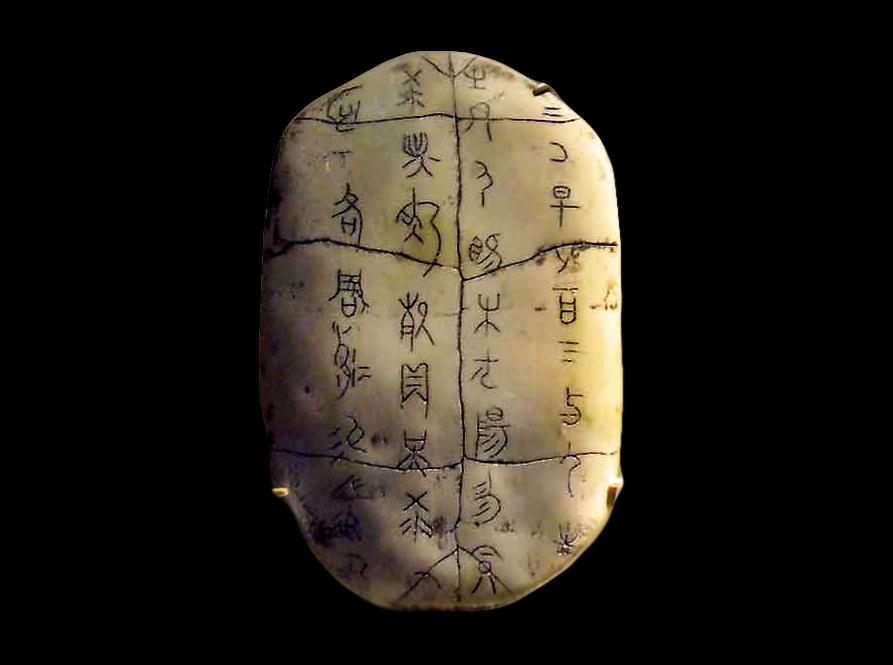

Divination was often performed by the use of "oracle bones" - typically the scapula of an ox or a sheep, or the shell of a turtle. A question and its answer(s) were inscribed on the bone, and a heated rod was pressed into the bone. The resulting pattern of cracks would be interpreted by a diviner. It was believed that the ancestors or some other spirits had responded with the answer.

Divination was often performed by the use of "oracle bones" - typically the scapula of an ox or a sheep, or the shell of a turtle. A question and its answer(s) were inscribed on the bone, and a heated rod was pressed into the bone. The resulting pattern of cracks would be interpreted by a diviner. It was believed that the ancestors or some other spirits had responded with the answer.

The script used on the oracle bones is the earliest known form of Chinese writing,

Archaeological evidence suggests that animal and human sacrifice were practiced during the Shang period. Also, in order to provide the dead ruler with comforts in the after-life, hundreds of horses and people, probably slaves, would be buried alive with the royal corpse.

The Shang rulers asserted their supremacy by taking on the role of high priests, and by leading the religious ceremonies and divination procedures. Sacrifices were made not only to Shang Di, but also to various natural powers such as the sun, and to the ancestors of the rulers.

During the Zhou dynasty (1050-256 BC) Shang Di, the High God, was regarded as so distant that he had little care for humanity and its affairs, and the concept of "Heaven", Tian, developed. Tian presided over the spirits of the dead, and gave a mandate to the Emperors (the Mandate from Heaven).

The concept of the Mandate from Heaven, and the ruler being the "Son of Heaven" was introduced by the rulers of the Zhou dynasty to validate their deposing the Shang dynasty - they claimed that the last Shang rulers had been so bad that Heaven had decreed their downfall.

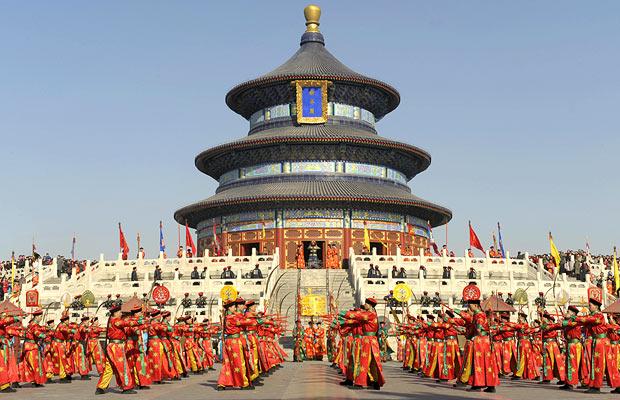

If a ruler was pleasing to Tian, things would go well with the land. If the ruler was unworthy the Mandate would be withdrawn and there would be famine, floods, other natural disasters, and rebellion. If this happened the ruler could be deposed and a more worthy ruler appointed. It was the ruler's duty to perform the annual sacrifices in the Temple of Heaven in the capital city (now called Beijing). This was so sacred a place that common people were not allowed there, and were not allowed even to watch the ruler's procession to the Temple to perform the sacrifices. At the winter solstice he sacrificed a red bullock, and offered jade, silk, wine and incense to Tian. This was supposed to guarantee the orderly behavior of nature through the year, and a bountiful harvest. During this period the ruler became regarded as the "Son of Heaven"

If a ruler was pleasing to Tian, things would go well with the land. If the ruler was unworthy the Mandate would be withdrawn and there would be famine, floods, other natural disasters, and rebellion. If this happened the ruler could be deposed and a more worthy ruler appointed. It was the ruler's duty to perform the annual sacrifices in the Temple of Heaven in the capital city (now called Beijing). This was so sacred a place that common people were not allowed there, and were not allowed even to watch the ruler's procession to the Temple to perform the sacrifices. At the winter solstice he sacrificed a red bullock, and offered jade, silk, wine and incense to Tian. This was supposed to guarantee the orderly behavior of nature through the year, and a bountiful harvest. During this period the ruler became regarded as the "Son of Heaven"

Although Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism became the leading religions for intellectuals, in the villages and farming communities, and among the people in general, the earlier folk religion continued, and developed with time.

Families still make ritual sacrifices of animals and food to deities, spirits, and ancestors at temples and shrines.

Although Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism became the leading religions for intellectuals, in the villages and farming communities, and among the people in general, the earlier folk religion continued, and developed with time.

Families still make ritual sacrifices of animals and food to deities, spirits, and ancestors at temples and shrines.

Shamans, who communicated with the spirit world in trances induced by fasting, drugs, incense, smoke, or dancing, were used by the rulers of the early dynasties, but had ceased to be used officially by the court by about 400 AD. They continue to the present day as folk healers, mediums, interpreters of dreams, and exorcists

Throughout China there are numerous shrines and temples to local deities as well as to some of the higher-ranking spiritual beings and gods and goddesses.

Throughout China there are numerous shrines and temples to local deities as well as to some of the higher-ranking spiritual beings and gods and goddesses.

People tend to visit the shrine of whichever deity they think will help with their current situation or problem.

At the top of the hierarchy of Heaven is the Jade Emperor, whose cult appeared in the 9th century AD, from unknown origins. He is revered as the supreme judge and ruler of Heaven, with power over all other deities. The Jade Emperor is regarded as such a remote figure that he can only be approached through intermediaries, so there are not many temples to him. He is usually portrayed in the robes and head-dress of the early Chinese emperors. He is the mouth-piece for the Three Pure Ones - three Daoist cosmic forces to whom Daoist priests will occasionally offer sacrifices but who are not generally worshipped.

At the top of the hierarchy of Heaven is the Jade Emperor, whose cult appeared in the 9th century AD, from unknown origins. He is revered as the supreme judge and ruler of Heaven, with power over all other deities. The Jade Emperor is regarded as such a remote figure that he can only be approached through intermediaries, so there are not many temples to him. He is usually portrayed in the robes and head-dress of the early Chinese emperors. He is the mouth-piece for the Three Pure Ones - three Daoist cosmic forces to whom Daoist priests will occasionally offer sacrifices but who are not generally worshipped.

One of the most popular deities is the goddess Guanyin - the goddess of mercy, and the special guardian of women and children. Women pray to her for children. She is often portrayed as a woman in a white robe, sometimes holding a baby, sometimes holding a willow branch and a vase, and sometimes as a figure with a thousand eyes and arms. Guanyin was originally the male Buddhist bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, but he was transformed by popular Chinese religion into a female figure.

One of the most popular deities is the goddess Guanyin - the goddess of mercy, and the special guardian of women and children. Women pray to her for children. She is often portrayed as a woman in a white robe, sometimes holding a baby, sometimes holding a willow branch and a vase, and sometimes as a figure with a thousand eyes and arms. Guanyin was originally the male Buddhist bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, but he was transformed by popular Chinese religion into a female figure.

Another deity, very popular with fishermen, is the goddess Mazu. According to one legend, Mazu was the daughter of a fisherman in south China in the 11th century. When her father and two brothers were in danger in a storm on the sea Mazu's soul left her body and went to save them. She had managed to draw her brothers' boat to safety, but then her mother found her apparently lifeless body and shook her arm in panic. Mazu's soul had to let go of her father's boat and return to her body. When her brothers returned home they recounted seeing Mazu's shape in the storm, and how their father's boat had been lost.

Another deity, very popular with fishermen, is the goddess Mazu. According to one legend, Mazu was the daughter of a fisherman in south China in the 11th century. When her father and two brothers were in danger in a storm on the sea Mazu's soul left her body and went to save them. She had managed to draw her brothers' boat to safety, but then her mother found her apparently lifeless body and shook her arm in panic. Mazu's soul had to let go of her father's boat and return to her body. When her brothers returned home they recounted seeing Mazu's shape in the storm, and how their father's boat had been lost.

The local fishermen began to carry statues of her on their boats for protection when they went to sea. Her cult grew over the years until in the 17th century she was proclaimed as the Empress of Heaven and a consort of the Jade Emperor. She is still a very popular goddess in China and Taiwan.

At the local level, each community has a local god, called Tudi Gong, who resides in a shrine in the village. People make small offerings to him at the times of the new and full moons, and perhaps daily incense. Tudi Gong's duties are to look after his community by taking care of ghosts and by keeping the peace. The people report incidents and events such as births, marriages and deaths, and Tudi Gong passes on the information to his spiritual superiors. Tudi Gong is portrayed as an elderly man with a long white beard and the robes of a bureaucrat.

At the local level, each community has a local god, called Tudi Gong, who resides in a shrine in the village. People make small offerings to him at the times of the new and full moons, and perhaps daily incense. Tudi Gong's duties are to look after his community by taking care of ghosts and by keeping the peace. The people report incidents and events such as births, marriages and deaths, and Tudi Gong passes on the information to his spiritual superiors. Tudi Gong is portrayed as an elderly man with a long white beard and the robes of a bureaucrat.

-di means "god", gong is the title for a bureaucrat, so his name means "Bureaucrat-god Tu"

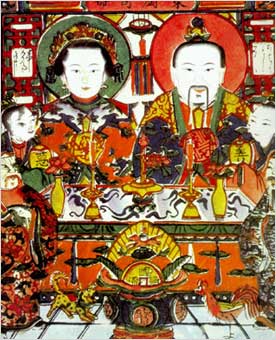

At the family level, most families have a picture of the Kitchen God, Zao Jun above their stove. The picture often includes his wife (or wives) and children.

At the family level, most families have a picture of the Kitchen God, Zao Jun above their stove. The picture often includes his wife (or wives) and children.

The Kitchen God seems to have developed from an earlier Fire god at the time when the brick oven was invented.

The Kitchen God looks after his family, and makes an annual report on them to the Jade Emperor. On the 23rd or 24th day of the last month of the year his family offer him sweet sticky treats so that his mouth will be stuck or he will only say sweet things, then they send him to the Jade Emperor by burning the paper picture of him which had been above the stove through the year. Then they put up a new picture of the Kitchen God and start the year over.

The Kitchen God looks after his family, and makes an annual report on them to the Jade Emperor. On the 23rd or 24th day of the last month of the year his family offer him sweet sticky treats so that his mouth will be stuck or he will only say sweet things, then they send him to the Jade Emperor by burning the paper picture of him which had been above the stove through the year. Then they put up a new picture of the Kitchen God and start the year over.

One story which is popular, and which is used to illustrate the principles of Daoism, is the story of Hundun, the Cosmic Gourd, the essence of Chaos and boundless potential.

Hundun is sometimes represented as a creature with legs but no face, but more often as a stylized gourd. The many seeds inside the gourd represent the many possibilities which have not been explored.

Hundun is sometimes represented as a creature with legs but no face, but more often as a stylized gourd. The many seeds inside the gourd represent the many possibilities which have not been explored.

The story is that Hundun was the King of the Center, and had none of the seven orifices of other creatures (eyes, ears, mouth, nose, anus). Hundun was kind and generous to King Fast of the North and King Furious of the South. His kindness was spontaneous and natural, but Kings Fast and Furious thought that they would lose face if they did not repay Hundun in some way. So they determined to give him the orifices like all other creatures. They visited him each day, and each day they bored an extra hole in him. On the seventh day Hundun died.

The point of the story was that King Fast and King Furious acted contrary to the Dao, and did not accept the spontaneity of Hundun, but were bound by rules and regulations. Hundun, like the gourd full of seeds, represents the myriad opportunities which should not be restricted and repressed by legalism.

Worship in Chinese tradition may take place in the home, at shrines, in temples, or at certain sacred places such as mountains, streams, and caves.

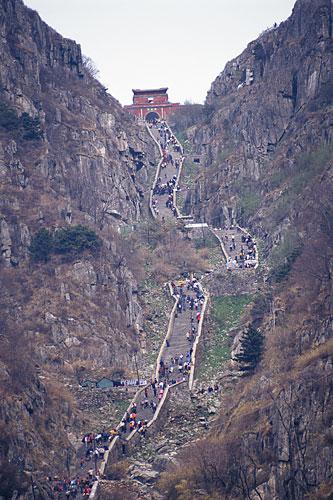

There are Five Sacred Mountains in China, the most famous being Mount Tai or Taishan (Shan means Mountain). Mount Tai has been a place of worship for at least 3,000 years, dating back to the Shang dynasty, and is one of the most important ceremonial centers of China. In 219 BC the First Emperor of China held a ceremony at the summit to proclaim the unity of his empire, and later emperors came there to make sacrifices. Each year, millions of Chinese make a pilgrimage to Mount Tai. There is a large temple at the foot of the mountain and several others on the sides of the mountain. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

There are Five Sacred Mountains in China, the most famous being Mount Tai or Taishan (Shan means Mountain). Mount Tai has been a place of worship for at least 3,000 years, dating back to the Shang dynasty, and is one of the most important ceremonial centers of China. In 219 BC the First Emperor of China held a ceremony at the summit to proclaim the unity of his empire, and later emperors came there to make sacrifices. Each year, millions of Chinese make a pilgrimage to Mount Tai. There is a large temple at the foot of the mountain and several others on the sides of the mountain. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Chinese Temples are usually built by private donations or by local societies rather than by religious authorities. They are administered by a temple association of local lay people, who hire religious specialists, such as Daoist or Buddhist priests, to perform ceremonies. They may also employ mediums and exorcists.

Chinese Temples are usually built by private donations or by local societies rather than by religious authorities. They are administered by a temple association of local lay people, who hire religious specialists, such as Daoist or Buddhist priests, to perform ceremonies. They may also employ mediums and exorcists.

The temple functions as a community center, where local affairs may be discussed, musical and theatrical performances given, and other social events take place.

They may contain statues of popular gods, of the Buddha, Guanyin and other bodhisattvas, and Confucius. Worship is generally informal - the worshipper may offer incense, food, and "spirit money". At other times the community may gather for a special celebration such as Chinese New Year or one of the other annual festivals.

The primary criterion for participation in Chinese traditional religion is not so much to "believe" in any particular dogma, or to be "converted" from one world-view to another, but to belong to a local religious group or village, and to take part in the rituals.

Determining the sacred power of a place, and the proper orientation for a building, tomb, or other structure, is the performed by the ancient art of Feng Shui. This is important so as to ensure harmony with the natural order of the world.

Chinese traditional views about death tend to focus on the continuity of the family. Members of one generation die and pass into an ancestral world similar to the current world, but there is still a connection to members of the next generation. With the advent of Buddhism the concept of karma and the possibility of an individual attaining enlightenment or nirvana has had some influence on popular ideas of death and the after-life, but Chinese traditional religion does not seem to look forward to a personal relationship with any of the deities or to an existence at a higher spiritual level after death.

The yin-yang concept of the cosmos has guided Chinese ideas about the soul. Traditional thought is that there are two souls - the po soul, which reflects the yin (feminine) principle, and the hun soul (masculine) which reflects the yang principle. As long as the hun and po are united within a body, the body lives. When the hun and po separate, the body dies. A dead body becomes cold because the warm hun has risen and departed.

The po soul or body-soul (yin principle) is linked to the body at the time of conception. It gives physical form to the body and is sustained by eating food. It remains on earth after death. If the funeral rites are performed properly the po soul will remain in the grave. However, if the rites are not correctly performed, or if the living generation displeases the po soul, it may become a ghost and cause trouble for the family, or sometimes a "Hungry Ghost", and cause trouble for the whole community.

The hun soul (yang) comes into existence at the time of birth, and is sustained by breathing. It represents the spiritual and intellectual aspects of a person. At death it leaves the body and goes to the place of departed spirits until it moves into the ancestral tablet prepared for it by the family. The world of departed spirits is generally thought of as a dark undefined place, but is sometimes referred to as Tian - called "Heaven", but having little in common with Western ideas of heaven.

The departed spirits (those of the ancestors of a family) need money, food, automobiles, and all the other comforts of earthly life. The current generation tries to supply these by burning paper joss - paper money and models of articles which the ancestors might like.

The departed spirits (those of the ancestors of a family) need money, food, automobiles, and all the other comforts of earthly life. The current generation tries to supply these by burning paper joss - paper money and models of articles which the ancestors might like.

Some of the Daoist philosophers taught that there were multiple hun and po souls - maybe even as many as three hun and seven po, though this does not seem to be a widespread idea in modern China.

Funerals are usually performed by the eldest son of the deceased.

When someone dies, all the statues of Chinese gods in the house are covered with red paper (so that the gods will not see the corpse). All mirrors are removed, because if anyone were to see the coffin reflected in a mirror it would mean that there would be another death in the family soon.

The body is washed and dressed in fine clothes which may be white, black, blue, or brown - red, the color of joy, is forbidden. If a corpse were dressed in red the soul would become a ghost and haunt the family. All the other clothes that were worn by the deceased are burned.

The dressed corpse is put in a rectangular coffin, which is placed according to rules of Feng Shui in or outside the house for a Wake. Where the family members stand, and what color clothes they wear are governed by a series of rules. An altar is prepared at the foot of the coffin, with a white candle and burning incense. The mourners may burn paper joss on the altar for the deceased.

The dressed corpse is put in a rectangular coffin, which is placed according to rules of Feng Shui in or outside the house for a Wake. Where the family members stand, and what color clothes they wear are governed by a series of rules. An altar is prepared at the foot of the coffin, with a white candle and burning incense. The mourners may burn paper joss on the altar for the deceased.

The wake usually lasts for at least one day, during which time the hun soul departs.

After the Wake there is the Funeral and a period of mourning, which may last for 49 days - seven periods of seven days each.

The coffin is nailed shut and yellow and white paper put over it to protect it from dangerous spirits. There are more rituals for closing the coffin, but people face away and do not watch the process because that would bring bad luck. The coffin is carried in a funeral procession with loud music (to scare away dangerous spirits) to a burial place near, but outside, the village. Often a Buddhist or Taoist priest will be called in to perform a funeral ritual.

The time and place of the funeral, and the orientation of the grave are important for the repose of the po soul, and should be determined by a practitioner of Feng Shui.

A bereaved family wears white, the color of mourning. Red, the color of joy, may not be worn. After the funeral the mourners burn the clothes they wore.

The family prepares an ancestral tablet for the deceased and installs it in the ancestral altar.

The family prepares an ancestral tablet for the deceased and installs it in the ancestral altar.

The ancestral altar in the home normally contains the ancestral tablets for the parents and grandparents of the family. The family usually offers incense twice a day, and food and spirit money at the times of the new moon and full moon, on holidays, and on the anniversary of the ancestor's death. The ancestral spirit consumes the "essence" of the food, and leaves the coarse material substance for the family to enjoy later.

Ancestral tablets for earlier generations are kept in an Ancestral Temple, which may be quite large and ornate.

Ancestral tablets for earlier generations are kept in an Ancestral Temple, which may be quite large and ornate.

Chinese traditional religion teaches that, just as there are mutual obligations in a living family to care for and provide for one another, so also there are mutual obligations between the living and the dead members of a family. The living members must care for the ancestors and provide for their needs, and the ancestors must care for the living and give them guidance and a good quality of life. If the living continue to provide for the dead, by giving them a proper burial, correct mourning rites, and continuing offerings of food and gifts, then the ancestors will continue to help them. The ancestors are remembered at all the family reunion feasts which are associated with the Festivals of the year - they are honored guests at every family reunion.

However, if the living members do not perform the rites properly, or forget the offerings, then the po soul will cause troubles such as disharmony in the family, bad luck, ill-fortune or other disasters. A po soul which is neglected may become a "Hungry Ghost" and attack a whole community or village. For this reason, the Chinese have a special Festival every year, the Hungry Ghost Festival, when food and entertainments are provided for the Hungry Ghosts, and Buddhist or Daoist priests conduct ceremonies and exhort the Ghosts to repent and enter the Buddhist "Pure Land".

The Chinese calendar is a complex system with cycles of sixty years, twelve years (the Chinese Zodiac), and one year. The Chinese year combines both lunar and solar calendars - the main points of the year are marked by the solstices and equinoxes which determine the beginning of seasons and which are regulated by the Yin-Yang variations.

Traditional Festivals are held throughout the year, starting with the Chinese New Year.

Copyright © 1999 Shirley J. Rollinson, all Rights Reserved