Images in the text are linked to larger photos - click on them to see the larger pictures.

Hover the mouse over the images to see their captions.

Jainism is held by Jains to be a collection of eternal and unchanging truths, and therefore to have no history, in the sense of a definite beginning in time. However, Jain tradition teaches that, throughout the history of the present cycle of the world, there have been 24 spiritually enlightened beings, called Tirthankaras (ford-makers), who have spent their lives teaching mankind the path to liberation from karma.

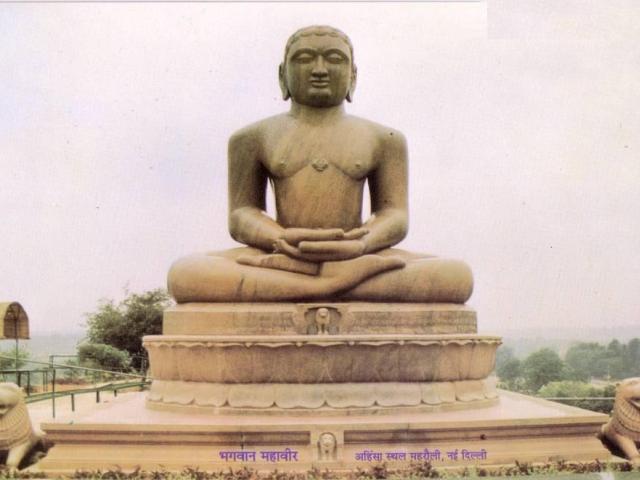

The earliest Tirthankaras are believed to have had enormously long life-spans, and to have lived billions of years ago. Each succeeding Tirthankara had a shorter life-span than the preceding one. The twenty-fourth (and last of this world's cycle) was Mahavira (a title given to him, meaning "Great Hero"), who is believed to have lived for 72 years, from 599-527 BC. (Some scholars put his dates a century later, 499-427 BC.)

Mahavira may have been a contemporary of the Buddha. They both stem from the same traditions of Hinduism.

When he was 30, Mahavira renounced his status as a royal prince, and set out in search of the path to liberation from the cycle of rebirth, and freedom from suffering for all beings. After twelve years of grueling and intense ascetic practice, he attained a state of perfect freedom and knowledge known as kevala j˝ana.

When he was 30, Mahavira renounced his status as a royal prince, and set out in search of the path to liberation from the cycle of rebirth, and freedom from suffering for all beings. After twelve years of grueling and intense ascetic practice, he attained a state of perfect freedom and knowledge known as kevala j˝ana.

Over the course of the next thirty years, Mahavira developed a following of monks, nuns, and laypersons which became the nucleus of the Jain community. Mahavira died at the age of 72.

Through the following centuries, Jains spread slowly through India, developing a variety of groups with varying teachings. The earliest extant scriptural texts (there were probably earlier ones, which have not survived) date to around 200 BC.

Somewhere around AD 200, the Shvetambara and Digambara branches of Jainism split from one another.

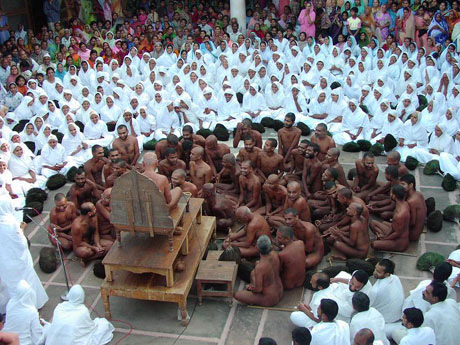

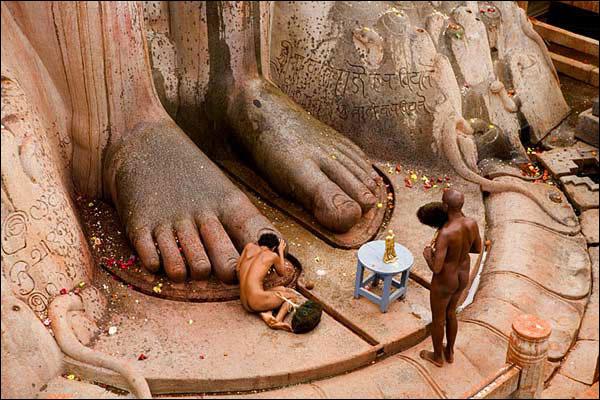

This schism is due to differing interpretations of the vow of non-possession, taken by all Jains. Digambara (sky-clad) Jain monks do not wear any clothes. Their only possession is a whisk made of dark peacock feathers (peacocks shed their feathers - they do not need to be plucked), which is used to sweep the ground where a monk walks or the space on which he is about to sit in order to prevent the accidental killing of insects. Digambara nuns wear simple white robes and are not permitted to practice nudity.

This schism is due to differing interpretations of the vow of non-possession, taken by all Jains. Digambara (sky-clad) Jain monks do not wear any clothes. Their only possession is a whisk made of dark peacock feathers (peacocks shed their feathers - they do not need to be plucked), which is used to sweep the ground where a monk walks or the space on which he is about to sit in order to prevent the accidental killing of insects. Digambara nuns wear simple white robes and are not permitted to practice nudity.

Shvetambara (white-clad) Jain ascetics wear simple white robes. They see non-possession as relating to one's inward attitude, and do not require the radical renunciation that the nude Digambara monks exhibit.

The "Golden Age" of Jain culture, with major Temples and artistic achievement is regarded as occurring around AD 1,000-1,200.

A major division occurred in the Jain community occurred when a Jain lay scholar, Lonka Shah (c. 1400-1500), came to believe that the use of images in worship violated the principle of non-violence. Under his influence another two groups formed - the Terapanthis and the Sthanakavasis. The Terapanthis believe that monks and nuns may live in monasteries, whereas the Sthanakavasis believe that building a monastery involves violence to the environment and creates a sense of ownership towards the structure.

Jainism was confined to India for centuries, because Jains do not travel far because they do not wish to injure small life-forms or disturb their environment. However, from about 1900 onwards, Jains migrated to various parts of the world, particularly to Britain and North America, and a growing number of temples and other Jain institutions were established world-wide.

In 1970 a Shvetambara monk, Chitrabhanu, became the first monk in modern history to break the traditional ban on overseas travel in order to spread Jain values globally. To do so, he had to renounce his vows as a Jain monk and give up his position as a leader of a Jain community in India.

In 1970 a Shvetambara monk, Chitrabhanu, became the first monk in modern history to break the traditional ban on overseas travel in order to spread Jain values globally. To do so, he had to renounce his vows as a Jain monk and give up his position as a leader of a Jain community in India.

Beliefs of Jainism

According to traditional Jain belief, the universe has always existed and will always exist. It was never "created", so there is no Creator.

However, Jains do have a concept of the divine, believing it to be the essence of the soul of every being. Jains believe that the divine is any soul that has become liberated and has realized its intrinsic nature as infinite bliss, knowledge, energy, and consciousness.

Jains believe that souls, (called Jiva - "conqueror") are all eternal, uncreated, and indestructible, and one inhabits every living thing. The Jiva are not fundamentally connected to the body they inhabit and they will take on a new body whenever the body they inhabit dies.

There are four general states or types of being into which a jiva can be born : human; animal or plant; heavenly being; or hellish being. Heavenly beings and hellish beings are not divine, gods, angels, or demons in the Western sense - they are merely bodily forms which inhabit other levels of the cosmos.

Jains rank beings according to the number of senses by which they are thought to experience the world :

- Five senses - humans, animals, birds, reptiles, heavenly beings, hellish beings.

- Four senses - flies, bees, scorpions, crickets, spiders

- Three senses - ants, lice

- Two senses - worms, leaches, microbes

- One sense - plants, water, air, earth, sand, clay, rain drops, fire, flames

For the Jains, "God" is any soul that has achieved liberation. "Each of these souls exists in identical perfection, and so is indistinguishable from any other such soul. Due to this identity of perfection, God for the Jains can be understood as singular. Because there are many liberated souls, God can also be understood as plural" (Cort, John. 2001. Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India, p.23).

Jains believe that the main aim of life is the realization of the intrinsic divinity of one's own soul. Souls are intrinsically divine - intrinsically joyful and perfect. However, their divinity has been obscured by the effects of karma.

Jains understand karma rather differently than Hindus and Buddhists. Rather than being just the law of moral consequences - "you reap what you sow", Jains think of karma as tiny particles of an actual substance - a non-living "thing", (ajiva) - which sticks to the living soul (jiva). To a Jain, karma can be good, or bad. A being's passions and activities cause its jiva to vibrate, and the vibration attracts the karma, which then bond to the jiva.

Peaceful actions, aimed at alleviating suffering or doing good for others, bring good karma to the soul.

Violent, angry passions resulting in harmful thoughts, words, or actions are the worst, attracting the most obscuring and painful varieties of karma to the soul.

However, any kind of karma is a load on the soul, and the ultimate aim is to eliminate all karma. One must strive to act with calm equanimity, and without anxiety for the outcome of one's action, in order to achieve a state of perfect freedom.

The Digambaras see monastic nudity as necessary for liberation. Because nuns are not allowed to follow this practice, Digambara tradition teaches that in order for a woman to become liberated, she must be reborn as a man.

Shvetambaras reject this view, and hold that both Mahavira's mother, and Mallinatha, the nineteenth Tirthankara, were women who attained liberation.

The Jain cosmos

Jains believe that the universe and everything in it has always existed and will never be destroyed. It operates entirely on its own without being sustained by or intervened in by gods or a Creator.

Jains picture the universe as consisting of several layers, in three main groups - sixteen layers of heavens, then the "middle world" where humans live, and below that seven levels of hells. The levels of hell get colder as they go further down. Souls which have been extremely cruel are reborn in one of the hells, where they fight one another and are tortured. They do not remain in hell permanently, though they may stay there for billions of years. When they have been punished sufficiently they are reborn into the normal world.

There is a tiny region above the heavens, which is the abode of souls which have achieved liberation from karma.

The Jain concept of time

Jains believe that time has neither beginning nor end - it proceeds in an endless cycle, called a Kalchakra, turning like a wheel. Jain texts do not give a specific length of time for a Kalchakra, but indicate that it is an incomprehensibly long period.

Jain texts speak of periods of time called palyopama (a pit of years), and sagaropama (an ocean of years). A palyopama is described as the amount of time it would take to empty a circular pit that is one yojan (probably about eight miles) in diameter and one yojan deep, and full of fine hairs, if someone carried away one hair every hundred years. A sagaropama is ten quadrillion (10,000,000,000,000,000) palyopama.

A full cycle consists of an ascending series of six periods, and a corresponding descending series of six periods. The periods at the top of the wheel are the longest, lasting for 400 trillion sagaropama, and are times of peace, prosperity, morality, and happiness. People living in this period live for three palyopama and are six miles tall.

A full cycle consists of an ascending series of six periods, and a corresponding descending series of six periods. The periods at the top of the wheel are the longest, lasting for 400 trillion sagaropama, and are times of peace, prosperity, morality, and happiness. People living in this period live for three palyopama and are six miles tall.

As periods approach the bottom of the wheel they become shorter, and conditions for people become worse. The lowest period is a time of terrible troubles and sorrow, chaos, poverty, and immorality. People living in this period will only live for about twenty years, and will be about six inches tall.

According to the Jain teachings, we are now living in the fifth period of the descending cycle. It is impossible for people living in the lower periods to attain liberation - they have to hope to live through sufficient "good" lives to reach an acceptable level when the wheel begins to turn upward, so that then they can achieve liberation.

The Jain Symbol

The symbol of Jainism is a picture of the shape of the universe, with other symbols within it that indicate various aspects of the religion. The eight-sided figure is sometimes described as that of a man. The bottom portion represents the layers of the hells, the narrow middle section represents the "middle world" where we live now. The top portion represents the layers of heavens.

The symbol of Jainism is a picture of the shape of the universe, with other symbols within it that indicate various aspects of the religion. The eight-sided figure is sometimes described as that of a man. The bottom portion represents the layers of the hells, the narrow middle section represents the "middle world" where we live now. The top portion represents the layers of heavens.

The arc at the top represents Siddhashita - the highest heaven, abode of liberated souls. The dot within the arc represent a liberated soul. The three dots below represent the Three Jewels of Jainism. The swastika has many meanings - its four arms represent the four attributes of a pure soul (Infinite Perception, Infinite Knowledge, Infinite Power, Infinite Bliss), or the four types of beings which souls can inhabit (human beings, animal beings, heavenly beings, hellish beings), or the four groups of the Jain community (monks, nuns, laymen, laywomen)

The open hand represents fearlessness. The wheel in the palm of the hand represents the cycle of rebirth, the 24 spokes represent the 24 Tirthankaras. The word in the center of the wheel is ahimsa (non-violence) as the supreme command.

The words below can be translated as "Souls render service to one another"

The Three Jewels of Jainism

The Three Jewels of Jainism are

- Right Vision, or Right Faith - a Jain must accept the concept of reality presented in the Jain scriptures, and try to distinguish the true from the false.

- Right Knowledge

- Right Conduct

Practices and Rituals of Jainism

Jain moral and ritual practices aim to cultivate a state of equanimity, and to purge the karma that currently adheres to the soul.

The moral principles of Jainism are expressed in the Five Great Vows, which monks and nuns take in an extreme form called mahavrata, and laypersons take in a less extreme form called anuvratas

- ahimsa : nonviolence in thought, word, and deed

The great vow of ahimsa is very strict. Some monks and nuns wear a "muhpatti", or mouth-shield, to avoid ingesting tiny flies or other life forms. The lesser vow entails no deliberate killing of any living thing, and the observance of a vegetarian diet. Non-violence also includes verbal insults, which cause hurt to another person, or approving of a violent act, or encouraging someone else to perform a violent act, or wanting someone else to suffer. Even carelessness is related to the desire to commit violence. - satya : telling the truth

- asteya : non-stealing - without the permission of the owner they will not take anything from anywhere.

- brahmacharya : restraint in the area of sexuality. Monks ans nuns will not touch a person of the opposite sex.

The great vow of brahmacharya entails celibacy for ascetics, but the lesser vow is for marital fidelity for laypersons - aparigraha : non-ownership, or non-attachment

The great vow of aparigraha forbids ownership of anything whatsoever for ascetics, who do not technically own the items that they use, such as the whisk (to brush insects out of their path), bowl, and clothing. Digambara ascetics do not even wear clothes. The lesser vow of aparigraha for laypersons is to live simply and to avoid greed or extravagance in regard to personal possessions.

Digambara monks are governed by many other rules, including eating and drinking only once a day, eating only while standing, eating from their hands (without a utensil), plucking all the hair off their heads once or twice a year, and sleeping only on a wooden pallet or on bare earth.

Shvetambara monks are allowed to sleep on a woolen blanket, and sit on a woolen mat.

Jain monks and nuns do not cook their own food, and do not get all their food for the day at one house - they go to several homes of Jains or other vegetarians, and are given a small amount of food which has already been prepared.

Jainism developed a system of logic to deal with the diversity of worldviews it encountered in India. This is expressed in its "doctrine of relativity" (not the same as Einstein's theory of relativity). The Jain view is called anekanta-vada, which means the "non-one-sided doctrine", or the doctrine of the complexity of reality. This states that reality is complex, or multi-faceted. All things have infinite aspects. No phenomenon can be reduced to a single concept.

Jain ritual

Jain Ritual is seen as a form of meditation, aimed at purging karma from the soul and preventing further karma from attaching itself.

Superficially, many Jain rituals appear to have the same structure as Hindu rituals. The majority of Jains are image-worshiping (Murtipujaka) Shvetambaras, who practice the worship of images, or murtipuja. Digambara Jains also use images. Only Shvetambara Terapanthi Jains and Sthanakavasi Jains do not use image-worship.

Image worship includes abhishekha, or anointing, in which pure substances such as milk, yoghurt, sandal paste, or water are poured over the top of an image; arati, in which lit candles or lamps are waved in front of the image, usually to the accompaniment of singing and the ringing of a bell; and the offering of food to the image.

When Jains speak of "God", they refer to the liberated soul. Any liberated being is regarded as divine, and all liberated beings are one, because all souls have the same basic essence of infinite knowledge, consciousness, energy, and bliss. These souls did not create the world, nor do they assist others towards liberation, beyond teaching the practice of the path to liberation, and starting a community to follow the path. Honoring (or worshipping) an image of a liberated being is to pay homage to the divinity within oneself. It is a kind of meditation and affirmation of the worshipper's commitment to the Jain path.

The offering of food illustrates the difference between Jainism and Hinduism. Hindus offer food to an image of a divinity, and then eat the food themselves. Offering of food to Jain deities is understood as a form of renunciation - showing one's detachment from the things of this world. Food offered to Jain deities is not consumed by the Jain community, but must leave the community - usually as charity to the poor from the surrounding community (which, in India, is usually Hindu).

Another Jain ritual is "caitya-vandan", in which the worshipper prostrates himself before an image and recites hymns and mantras from Jain scriptural texts. Then the worshipper stands and silently recites the "Namokara Mantra", regarded as the most sacred of all Jain prayers :

Another Jain ritual is "caitya-vandan", in which the worshipper prostrates himself before an image and recites hymns and mantras from Jain scriptural texts. Then the worshipper stands and silently recites the "Namokara Mantra", regarded as the most sacred of all Jain prayers :

I bow before the worthy ones [the Jinas or Tirthankaras].

I bow before the perfected ones [all those who have attained liberation].

I bow before the leaders of the Jain order.

I bow before the teachers of the Jain order.

I bow before all the ascetics in the world.

Organization

There is no single, central institutional authority for Jains. The basic distinction is that between ascetics and laypersons. Ascetics (monks and nuns) are generally regarded as the ultimate religious authorities for Jains, and as embodiments of the ideals of Jainism. The ascetics are organized into regional branches known as gacchas. If a disagreement arises within a gaccha over a question of practice, a new gaccha is usually the result. Gacchas are further subdivided into successively smaller groups.

In the global Jain community outside India, lay leadership is becoming important. The running of Jain temples is usually by a board of lay trustees made up of prominent donors and persons willing to give of their time and energy to ensure the smooth running of the institution and the transmission of Jain values to the younger generation.

- 877-777 BC

- (traditional dating) of Parshvanatha, twenty-third Tirthankara

- 599-527 BC (traditional dating), or 499-427 BC (revised dating)

- Mahavira, twenty-fourth (and last) Tirthankara of our current era.

- 327 BC

- Alexander the Great invaded northwestern India, lamented that there were no more lands left to conquer, but was then forced to turn back by his army.

- 327 BC

- Death of Alexander the Great, followed by struggles for power throughout his Empire. In India, Chandragupta Maurya of Magadha took control

- 320-293 BC

- Reign of Chandragupta Maurya, founder of the Maurya Dynasty. According to Jain tradition, Chandragupta Maurya was a Jain layman. It is said that he became a Jain monk in old age, and died of voluntary self-starvation.

- ca. 200 BC

- Jains began to spread from northeastern India to the south and west. This is the time when the earliest extant Jain texts were written.

- ca. 100 BC

- Start of the division between Shvetamabara and Digambara Jains.

- 1000-1200 AD

- Jain "Golden Age" of Period of artistic, architectural, literary, and philosophical achievements. Major Jain temple construction.

- 1867-1901

- Rajacandra Maheta, founder of a Jain movement known as the Kavi Panth, and a spiritual adviser to Mahatma Gandhi

- 1970 AD

- - Chitrabhanu, a Shvetambara monk, broke the ban on overseas travel in order to spread Jain values globally. He participated in a conference on world religions at Harvard University.

- 1975

- Sushil Kumar traveled to the USA

- 1983

- Sushil Kumar established Siddhachalam, a Jain center in Blairstown, New Jersey

- 1914-1997

- Acharya Tulsi, a Terapanthi Shvetambara Jain leader, pioneer in socially engaged Jainism.

- 1980

- Acharya Tulsi founded the saman and samani orders of Jain ascetics, but without the traditional vows and ban on travel, so as to enable them to do the kind of global work pioneered by Chitrabhanu and Sushil Kumar.

Copyright © 2015 Shirley J. Rollinson, all Rights Reserved