RELG 433 - Biblical Archaeology

Minoans and Mycenaeans

Heinrich Schliemann and Arthur Evans

Images in the text are linked to larger photos - click on them to see the larger pictures.

Hover the mouse over the images to see their captions and copyright credits.

The Greek civilizations of the Bronze Age impact the development of cultures in the Holy Land, in that the Sea Peoples who invaded Egypt, and the Philistines who settled on the Mediterranean coast of Canaan, came from the Aegean at about the time of the Trojan War.

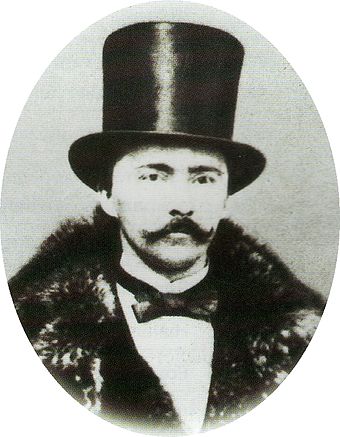

Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890), was a German American businessman who was fascinated by the story of Troy. Schliemann's father was a Lutheran pastor who was too poor to be able to give his son a University education. At age 14 Schliemann was apprenticed to a grocer, then he became a cabin-boy on a ship, and then he found employment as an office boy in Amsterdam.

In 1844 Schliemann joined an import/export firm, which sent him as their agent to St. Petersburg in 1846 (Schliemann was 24). Schliemann learned Russian and Greek in addition to his German and Dutch (it is claimed that in later life he spoke 13 languages).

In 1844 Schliemann joined an import/export firm, which sent him as their agent to St. Petersburg in 1846 (Schliemann was 24). Schliemann learned Russian and Greek in addition to his German and Dutch (it is claimed that in later life he spoke 13 languages).

Schliemann had a brother, Ludwig, who had emigrated to America and joined the gold rush to California. Ludwig became rich, but died in 1850, so Schliemann traveled to California to take care of his brother's estate. Schliemann started a bank and became rich himself, and sometime, probably about then, became an American citizen. In 1852 he sold his business and moved back to Russia, where he married a Russian girl, Ekaterina, and started a business marketing indigo dye, and later other commodities including ammunition for Russia during the Crimean War of 1854-1856. By 1858 Schliemann was a millionaire and decided to retire and devote himself to a search for Troy, which most scholars of the time regarded as a merely mythical place which had never really existed.

Schliemann moved to Paris in 1866 so that he could study at the Sorbonne. He moved his fortune to France, to invest in real estate, and asked his wife to join him there. She refused, so Schliemann returned to the USA in 1869 to obtain a divorce (easier to do there than in Europe). As soon as he obtained his divorce Schliemann left the USA and moved to Athens, which became his main home until his death. In 1869 Schliemann was awarded a doctorate for his studies in Greek and for his work suggesting that the mound of Hissarlik in Turkey was the site of ancient Troy. Schliemann decided that he wanted a Greek wife, and wrote to a Greek Orthodox bishop asking him to find a suitable girl for him - the main stipulation was that she should know Homer's poems. The bishop suggested one of his own relatives, young Sophia Engastromenos, who was still a schoolgirl. When Schliemann met her he recited a couple of lines from the Iliad; Sophia replied by reciting the next couple of lines from memory; they married that same year and then set off for the plain of Illium and the search for the site of Troy.

Schliemann was in fact not the first person to suspect that Hissarlik was the site of ancient Troy - an English family had lived near Hissarlik and owned land there for years - the Calvert family. At that time there were three Calvert brothers: Frederick, who was the British consul in the Dardanelles during 1846-1862; James, who was American consul; and Frank, who succeeded James as American consul. All the Calverts were interested in Troy, and all three talked about it with Schliemann. Frank had explored the region thoroughly, and by 1863 was hoping for funds to excavate Hissarlik for the British Museum. However, the committee at the British Museum would not even advance £100 for a preliminary investigation. In spite of that, Frank Calvert went ahead and bought part of the land of Hissarlik and went ahead with excavation in 1865. He found enough to show that there were parts of city walls and the remains of a temple in the mound; he lacked the funds to excavate further.

Schliemann visited Hissarlik for the first time in 1868 and met Frank Calvert, and became sure that Hissarlik was indeed the site of ancient Troy. A firman, or permission for an archaeological dig, had to be obtained from the Turkish government; Schliemann was able to do this, with the provision that half of the finds should be given to the Turkish archaeological museum, any ruins should be left in the condition in which they were found, and no structures were to be demolished. In the course of the dig Schliemann broke all these agreements; as a result the Turkish government became very suspicious of any foreign archaeologists. Schliemann started to dig in 1870, and continued for the next three years. His methods were drastic - he demolished anything that he considered not to be of interest (including what we now believe to have been some of the city walls dating to the Trojan War). In the course of this devastation, Schliemann and Frank Calvert had a falling-out, and Calvert refused to let Schliemann continue to excavate on the Calvert-owned part of the hill.

Schliemann excavated down to bedrock, and identified several layers corresponding to various ages or "cities". Schliemann was one of the first to number the strata on a dig - though his numbering system was the reverse of that currently in use. Schliemann numbered the strata from bedrock up, whereas modern digs number the strata starting at the top - the surface, or most recent. Schliemann thought that the Troy he sought was the second layer from bedrock - now known as Troy II, and probably dating to the Early Bronze Age - which had been destroyed by a great fire. In fact, the Troy of the Trojan War was probably Troy VI, which had been largely destroyed by later building and by Schliemann's destructive methods.

Schliemann excavated down to bedrock, and identified several layers corresponding to various ages or "cities". Schliemann was one of the first to number the strata on a dig - though his numbering system was the reverse of that currently in use. Schliemann numbered the strata from bedrock up, whereas modern digs number the strata starting at the top - the surface, or most recent. Schliemann thought that the Troy he sought was the second layer from bedrock - now known as Troy II, and probably dating to the Early Bronze Age - which had been destroyed by a great fire. In fact, the Troy of the Trojan War was probably Troy VI, which had been largely destroyed by later building and by Schliemann's destructive methods.

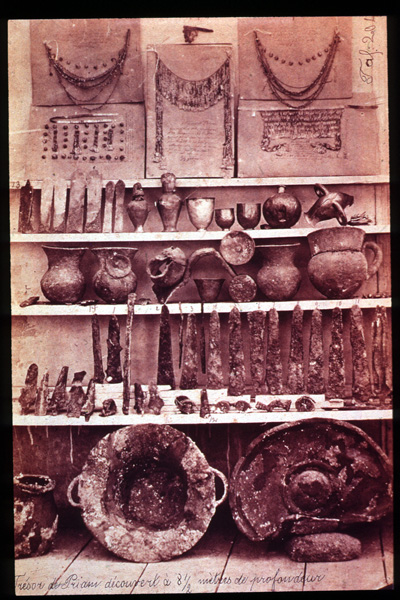

During the 1873 dig Schliemann found a great cache, which he called "the Treasure of Priam" after the King of Troy. The treasure consisted of copper cauldrons and lance-heads, cups made of gold, silver, and bronze, and thousands of articles of golden jewelry - bracelets, necklaces, head-dresses, rings, ear-rings, diadems.

During the 1873 dig Schliemann found a great cache, which he called "the Treasure of Priam" after the King of Troy. The treasure consisted of copper cauldrons and lance-heads, cups made of gold, silver, and bronze, and thousands of articles of golden jewelry - bracelets, necklaces, head-dresses, rings, ear-rings, diadems.

In defiance of his agreement with the Turkish government, Schliemann smuggled the Treasure out of Turkey, and across the Aegean to Athens.

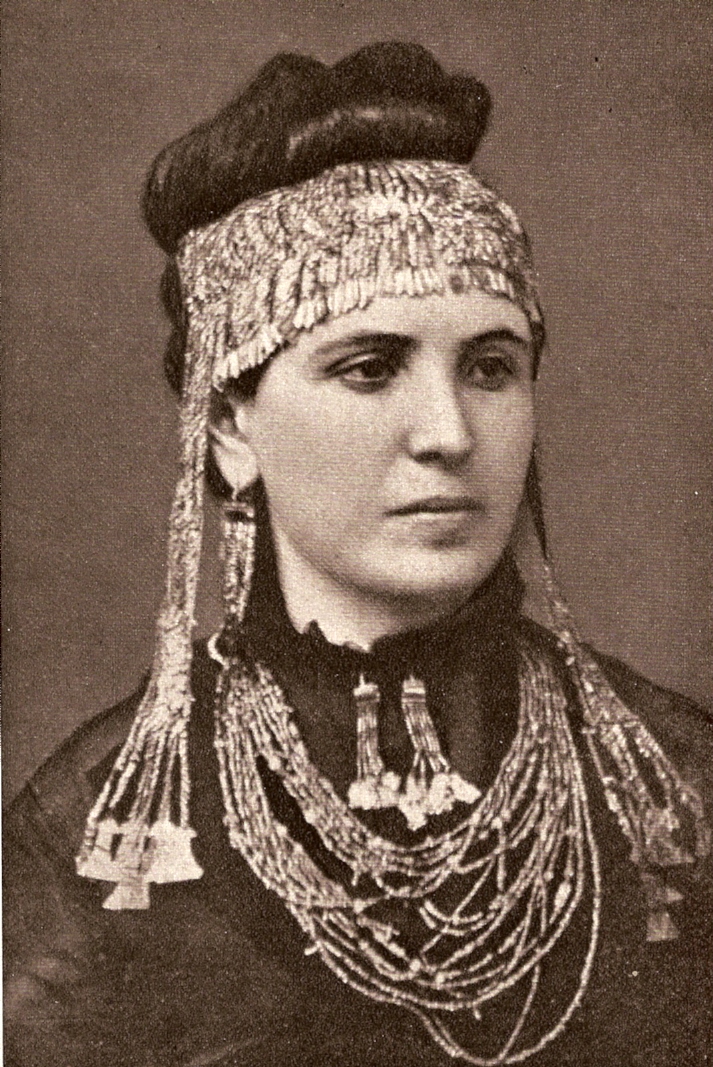

Sophia was photographed wearing "the Jewels of Helen" and the Turkish government imposed a large fine on Schliemann and refused him permission to continue the excavation. Schliemann claimed that he took the treasures to Athens so that they would form part of a Greek Museum, as he seems to have promised to Sophia. However, he offered them to various other museums, and eventually sold them to the Berlin Museum, much to Sophia's distress.

Sophia was photographed wearing "the Jewels of Helen" and the Turkish government imposed a large fine on Schliemann and refused him permission to continue the excavation. Schliemann claimed that he took the treasures to Athens so that they would form part of a Greek Museum, as he seems to have promised to Sophia. However, he offered them to various other museums, and eventually sold them to the Berlin Museum, much to Sophia's distress.

Schliemann was eventually allowed to return to Turkey and dig at Hissarlik and other places again, but he made no more such sensational discoveries as the Treasure of Priam.

Schliemann was also refused permission to dig in Crete, where he might otherwise have discovered the Minoan civilization.

As a footnote - the "the Treasure of Priam" was in the Berlin Museum until WW II, when the Russians took that part of the city, and the Treasure disappeared. For years it was believed that the Treasure had been looted by soldiers and was lost forever. Recently, the Russians have admitted to having the Treasure in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, where it is now on display; they refuse to return it to Berlin or to Turkey.

Heinrich Schliemann next turned his attention to mainland Greece, and the homeland of Agamemnon and the Achaean Greeks who had besieged Troy.

Heinrich Schliemann next turned his attention to mainland Greece, and the homeland of Agamemnon and the Achaean Greeks who had besieged Troy.

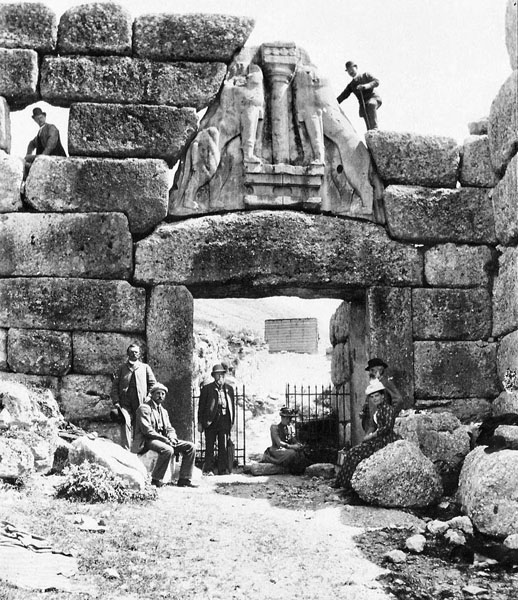

During 1876-1878 he excavated at Mycenae - with an official from the Greek government watching like a hawk in case he stole any treasures. Schliemann discovered a series of shaft-graves inside the citadel of Mycenae, which contained the bodies of nineteen adults and two children, covered in gold, and with golden grave-goods - cups, boxes, decorative plaques, and bronze daggers and swords. The faces of the men had been covered with golden masks, one of which Schliemann called "the Mask of Agamemnon". Schliemann had found a previously unknown Bronze Age civilization - the Mycenaeans. Later studies show that the Mycenaean shaft-graves date to the sixteenth century BC, and the great cyclopean walls of Mycenae date to the thirteenth century BC.

During 1876-1878 he excavated at Mycenae - with an official from the Greek government watching like a hawk in case he stole any treasures. Schliemann discovered a series of shaft-graves inside the citadel of Mycenae, which contained the bodies of nineteen adults and two children, covered in gold, and with golden grave-goods - cups, boxes, decorative plaques, and bronze daggers and swords. The faces of the men had been covered with golden masks, one of which Schliemann called "the Mask of Agamemnon". Schliemann had found a previously unknown Bronze Age civilization - the Mycenaeans. Later studies show that the Mycenaean shaft-graves date to the sixteenth century BC, and the great cyclopean walls of Mycenae date to the thirteenth century BC.

Schliemann undertook further excavations in Greece, at Ithaca (1878), Orchomenus, Boeotia (1881-82), and Tiryns (1884-85).

From 1882 onwards Schliemann was assisted by Wilhelm Dörpfeld. Dörpfeld had trained as an archaeologist, and he influenced Schliemann to refine his techniques.

In 1886 Schliemann visited the ruins of Knossos on the island of Crete, and realized that Knossos probably predated the Trojan War. In 1889 he tried to buy the land which contained the site, but was unsuccessful. He could not get permission to dig, so gave up and returned to Troy.

In 1890 Schliemann traveled to Germany for an operation on an infected ear. After the operation he left the hospital to travel through Europe to Greece, against his doctors' advice. He collapsed into a coma and died before reaching Athens.

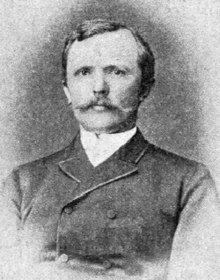

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940) was a German archaeologist who was one of the first to develop stratigraphic excavation and graphical documentation of archaeological excavations. He trained as an architect, but after graduation he became an assistant at a dig in Greece in 1877 and worked his way up to becoming the technical manager.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940) was a German archaeologist who was one of the first to develop stratigraphic excavation and graphical documentation of archaeological excavations. He trained as an architect, but after graduation he became an assistant at a dig in Greece in 1877 and worked his way up to becoming the technical manager.

In 1883 he met Heinrich Schliemann, who persuaded him to join the excavation of Troy. From 1884 to 1885 Schliemann and Dörpfeld excavated Tiryns, then from 1888 to 1890 they went back to excavating Troy. Dörpfeld excavated at the Acropolis in Athens during 1885-1890, Pergamon during 1900-1913, and the Agora of Athens in 1931.

In 1883 he met Heinrich Schliemann, who persuaded him to join the excavation of Troy. From 1884 to 1885 Schliemann and Dörpfeld excavated Tiryns, then from 1888 to 1890 they went back to excavating Troy. Dörpfeld excavated at the Acropolis in Athens during 1885-1890, Pergamon during 1900-1913, and the Agora of Athens in 1931.

Schliemann died in 1890, and Sophia Schliemann hired Dörpfeld to continue the excavation of Troy, where he found a series of nine cities, and identified Troy VI as the Troy of Homer.

Sir Arthur John Evans (1851-1941) excavated on the island of Crete, mainly at Knossos,

and uncovered the remains of the previously unknown Minoan civilization. Evans devoted considerable time and expense to the reconstruction of the most impressive feature of the civilization, the Palace.

Sir Arthur John Evans (1851-1941) excavated on the island of Crete, mainly at Knossos,

and uncovered the remains of the previously unknown Minoan civilization. Evans devoted considerable time and expense to the reconstruction of the most impressive feature of the civilization, the Palace.

Evans' early career was as a writer and reporter for the Manchester Guardian, which was a cover for work as a spy in the Balkans. The Ottoman Empire (of Turkey) was failing, the Serbs, the Herzogovinians were in revolt, the mainland Greece had already broken free of Ottoman rule, and Christians and Muslims were massacring one another. He was arrested and jailed several times, but usually managed to talk himself out of situations. During his travels he began to collect antiquities, and his interest in archaeology developed.

In 1878 Evans saw some of Schliemann's treasures from Troy, which were being exhibited in London. These aroused his interest to such an extent that he journeyed to Greece to see the sites of Tyrins and Mycenae, and to visit the Schliemanns in Athens.

In 1884 Evans was appointed Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and started to implement his plans to turn it into one of the leading archaeological museums in Europe.

Consequently, he journeyed to the Mediterranean again to look for antiquities. In 1893, in Athens, Evans' attention was drawn to a number of small seal-stones engraved with writing which he recognized as an undeciphered system of hieroglyphics. He learned that they came from the island of Crete, where Minos Kalokairinos, an amateur Cretan archaeologist, was digging at Knossos.

Consequently, he journeyed to the Mediterranean again to look for antiquities. In 1893, in Athens, Evans' attention was drawn to a number of small seal-stones engraved with writing which he recognized as an undeciphered system of hieroglyphics. He learned that they came from the island of Crete, where Minos Kalokairinos, an amateur Cretan archaeologist, was digging at Knossos.

The site of Knossos was already well-known, but excavation was blocked by the Turkish authorities, who wanted large sums of money for permits to dig, and who insisted that archaeologists buy the land before they could be awarded a permit to dig. Kalokairinos' family owned the land on which Knossos was situated, and he was able to dig some exploratory trenches before the Turkish authorities moved in and stopped him. In addition to this, revolts against Turkish rule in Crete had started in 1770, re-erupted in 1841 and 1858, led to the (unsuccessful) Great Cretan Revolution of 1866-1869, and further revolts in 1878, 1889, 1895, in 1897, leading to autonomy in 1898. Kalokairinos' house was burned during the 1866 revolt, and his collection of artifacts and his excavation notes were destroyed. Schliemann had tried to buy part of the land at Knossos but was unsuccessful. Evans visited Kalokairinos in 1894, and was able to buy part of the archaeological site, and again in 1898 when he was able to buy the rest of the site. In 1900 Evans finally was able to start a professional excavation of Knossos, and uncovered a vast complex of buildings now known as the Palace of Knossos or the Palace of Minos.

The site of Knossos was already well-known, but excavation was blocked by the Turkish authorities, who wanted large sums of money for permits to dig, and who insisted that archaeologists buy the land before they could be awarded a permit to dig. Kalokairinos' family owned the land on which Knossos was situated, and he was able to dig some exploratory trenches before the Turkish authorities moved in and stopped him. In addition to this, revolts against Turkish rule in Crete had started in 1770, re-erupted in 1841 and 1858, led to the (unsuccessful) Great Cretan Revolution of 1866-1869, and further revolts in 1878, 1889, 1895, in 1897, leading to autonomy in 1898. Kalokairinos' house was burned during the 1866 revolt, and his collection of artifacts and his excavation notes were destroyed. Schliemann had tried to buy part of the land at Knossos but was unsuccessful. Evans visited Kalokairinos in 1894, and was able to buy part of the archaeological site, and again in 1898 when he was able to buy the rest of the site. In 1900 Evans finally was able to start a professional excavation of Knossos, and uncovered a vast complex of buildings now known as the Palace of Knossos or the Palace of Minos.

Copyright © 1999 Shirley J. Rollinson, all Rights Reserved