RELG 433 - Biblical Archaeology

Course Notes

Module 3 - Problems in Biblical Archaeology

Images in the text are linked to larger photos - click on them to see the larger pictures.

Hover the mouse over the images to see their captions and copyright credits.

There are a number of problems in archaeology, of which everyone should be aware. Many of them stem from human ignorance or greed, or the pressure of political or economic situations in the Middle East.

Forgery

Forgery

As Museums and private collectors are willing to pay high prices for rare artefacts, so there is a growing industry for producing forgeries and fakes. Forgeries may be of a simple and crude sort, for sale to tourists in the Bazaar. However, some are extremely sophisticated, and may be accepted by Museums and other experts as genuine.

Probably the most famous suspected forgery is the "James' Ossuary". An ossuary is a stone or earthenware box to contain the bones of a dead person after the flesh has dried away - ossuaries were in common use in Palestine at the time of Jesus. The ossuary in this case was in a private collection - there is no record of where and how it was found. It was on display in the home of its owner, Oded Golan, when a visitor noticed a faint inscription scratched on one side. The inscription was in Hebrew, and said "James the brother of Jesus". Experts were called in, all sorts of tests were made, and initially most of the experts thought that the inscription was genuine - that it was made at the time of the New Testament, and that it might indeed refer to James the brother of Jesus. However, some experts were doubtful - the ossuary itself seemed to be of the right age, but there were questions as to whether the inscription had been scratched on at a later date, or whether the words "the brother of Jesus" had been added later. The Israeli police raided the home of the owner, and found equipment and supplies commonly used by forgers of antiquities, and a forgery trial dragged on for years. Eventually the Israeli court declared that the James' Ossuary might be genuine (though there is no proof that the "Jesus" of the inscription is Jesus Christ). The current view seems to be that the James' Ossuary belongs better in the category of "unprovenanced artifact" (see below)

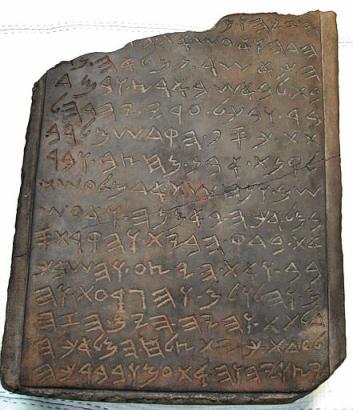

Another artefact - also in the hands of Oded Golan - is the "Jehoash Inscription", also known as the "Jehoash Tablet". This is a tablet with an inscription in Paleo-Hebrew, which claims to be a report of repairs to the First Temple by King Jehoash (aka Joash - II Kings, chapter 12; II Chron. 24:4-13). Various statements reported to have been made by Oded Golan are mutually inconsistent. One version is that he had bought the stone tablet from an antiquities dealer thirty years ago, and could no longer remember who sold it to him. He was 50 at the time of that statement, which would mean that he bought the tablet when he was about 20 - and these things are not cheap. However, the existence of the tablet was not made public until a few years ago. Oded Golan is also reported to have said that he is not the actual owner of the tablet, but he refuses to disclose who the real owner is.

Another artefact - also in the hands of Oded Golan - is the "Jehoash Inscription", also known as the "Jehoash Tablet". This is a tablet with an inscription in Paleo-Hebrew, which claims to be a report of repairs to the First Temple by King Jehoash (aka Joash - II Kings, chapter 12; II Chron. 24:4-13). Various statements reported to have been made by Oded Golan are mutually inconsistent. One version is that he had bought the stone tablet from an antiquities dealer thirty years ago, and could no longer remember who sold it to him. He was 50 at the time of that statement, which would mean that he bought the tablet when he was about 20 - and these things are not cheap. However, the existence of the tablet was not made public until a few years ago. Oded Golan is also reported to have said that he is not the actual owner of the tablet, but he refuses to disclose who the real owner is.

From an archaeological standpoint, the authenticity of the inscription is suspect - experts are not in complete agreement, but it appears that the letters seem to be a mixture of forms from different periods.

To make matters even worse, the Israeli police and the IAA (Israel Antiquities Authority) got their hands on both the Jehoash tablet and the James Ossuary. The Jehoash Tablet (accidentally) broke in two "when it was laid down gently" (it had been handled safely by a number of other people prior to that, without suffering damage)

![]() An earlier example of a forger, who made a fortune by dealing in forgeries, was Moses Shapira, who, in 1883, offerred to sell part of a scroll with what was acclaimed in the press as "the original text of Deuteronomy" to the British Museum, for £1,000,000. Shapira was a Polish Jew who converted to Christianity, settled in Jerusalem, and became an antiquities dealer. He made a fortune by selling 'antiquities' to early travelers to Palestine, often arranging to take them to excavate sites which he had salted with artefacts - which they were then very ready to buy from him. Ten years before his offer to the British Museum, and shortly after the discovery of the Moabite Stone in 1868, Shapira sold over a thousand 'Moabite' figurines and pottery to the Berlin Old Museum - and they were exposed as forgeries by a French archaeologist, Charles Clermont-Ganneau. After that, Clermont-Ganneau was suspicious of Shapira. Shapira refused to let Clermont-Ganneau examine the scroll fragments. Other experts were called in, and a vicious campaign of accusations and allegations began, including an anti-Semitic cartoon of Shapira in the British press. Finally the verdict was given that the scroll was a forgery. Shapira fled to Amsterdam, then to Rotterdam, where he committed suicide by shooting himself.

An earlier example of a forger, who made a fortune by dealing in forgeries, was Moses Shapira, who, in 1883, offerred to sell part of a scroll with what was acclaimed in the press as "the original text of Deuteronomy" to the British Museum, for £1,000,000. Shapira was a Polish Jew who converted to Christianity, settled in Jerusalem, and became an antiquities dealer. He made a fortune by selling 'antiquities' to early travelers to Palestine, often arranging to take them to excavate sites which he had salted with artefacts - which they were then very ready to buy from him. Ten years before his offer to the British Museum, and shortly after the discovery of the Moabite Stone in 1868, Shapira sold over a thousand 'Moabite' figurines and pottery to the Berlin Old Museum - and they were exposed as forgeries by a French archaeologist, Charles Clermont-Ganneau. After that, Clermont-Ganneau was suspicious of Shapira. Shapira refused to let Clermont-Ganneau examine the scroll fragments. Other experts were called in, and a vicious campaign of accusations and allegations began, including an anti-Semitic cartoon of Shapira in the British press. Finally the verdict was given that the scroll was a forgery. Shapira fled to Amsterdam, then to Rotterdam, where he committed suicide by shooting himself.

Shapira had left the scroll at the British Museum, who arranged for it to be auctioned to a bookseller. He sold it for £25, and it disappeared into a private collection. Later attempts to locate it indicate that it was probably destroyed in a fire in 1899.

Shapira claimed that he had acquired the scroll from an Arab who said that he had found it in a cave in the hills of Moab, east of the Dead Sea. When the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in 1947 there was immediate speculation that the scroll which Shapira had been trying to sell might have been part of the same collection, but it was no longer available for examination. However, the general opinion is that it had been a forgery, with only coincidental similarity to the Dead Sea Scrolls.

![]()

Frauds and Hoaxes and Ignorant Mistakes

Frauds and Hoaxes and Ignorant Mistakes

I would define a fraud or hoax as something that someone made or did, knowing that the article was not genuine, but without the intention of making money from the sale of the article. It might have started out as a joke, or someone might have been seeking publicity as the discoverer of something unusual.

There are several such examples - some in the USA, one even in New Mexico.

There are several such examples - some in the USA, one even in New Mexico.

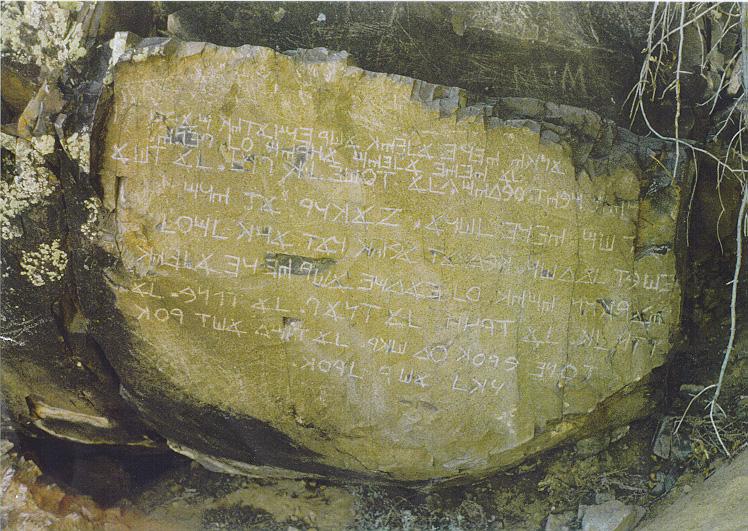

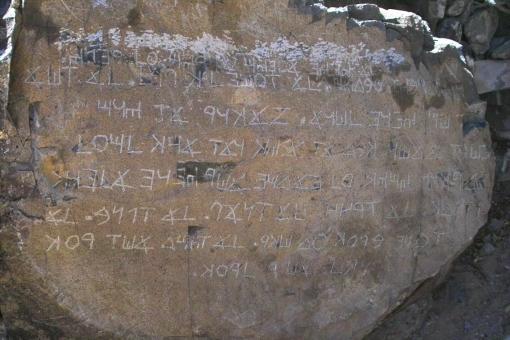

The Los Lunas Inscription is a long inscription on a rock in the region west of Los Lunas and south of Albuquerque. It is in some sort of paleo-Hebrew, and gives a version of the Ten Commandments. The Los Lunas inscription was first publicized in the 1980s by Barry Fell, and again in 1996 by Frank Hibben, professor of archaeology at the University of New Mexico (Albuquerque). Hibben took James Tabor, a leading Near Eastern archaeologist, to see the stone, and gave him an account of its discovery which Tabor believed and published. Almost all the evidence we have for its discovery and history comes from accounts by Frank Hibben.

Hibben claimed that he was taken to the stone in 1933 by a Native American, who told him that he had first seen it in 1880. Hibben

claimed that the inscription was covered by lichen and deposits which he cleaned away, but which he said indicated that the inscription was ancient.

There followed years of claims and counter-claims, analysis of the inscription, and theories of its origin. Analysis of the inscription showed that it contains not only Paleo-Hebrew characters, but also some resembling the Samaritan forms of Hebrew, and also some Greek letters. There are spelling mistakes, and the text of the Ten Commandments on the stone is different from the Masoretic text or the Samaritan text as we know them. Photos reveal that there is some spacing between words - which would be very unusual for an ancient inscription.

There followed years of claims and counter-claims, analysis of the inscription, and theories of its origin. Analysis of the inscription showed that it contains not only Paleo-Hebrew characters, but also some resembling the Samaritan forms of Hebrew, and also some Greek letters. There are spelling mistakes, and the text of the Ten Commandments on the stone is different from the Masoretic text or the Samaritan text as we know them. Photos reveal that there is some spacing between words - which would be very unusual for an ancient inscription.

The inscription and the rock have been scrubbed by amateurs several times, and chalked to show up the letters; in 2006 vandals erased the top line of the inscription.

The stone is on land belonging to the New Mexico State Trust Lands - photos of the stone have been taken down from their website.

The stone is on land belonging to the New Mexico State Trust Lands - photos of the stone have been taken down from their website.

Theories as to the possible origin of the inscription (if genuine) included Jews or Samaritans fleeing to America during times of persecution, or Mormons traveling through the region.

Until recently, Hibben's account was taken at face value; he was a respected professor at UNM, co-founder and director of the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, and funded a $3.5-million donation to UNM for the "Hibben Center for Archaeological Research". However, things started to unravel when a couple of Hibben's major research 'findings' were checked by others, and found to be erroneous and probably faked. He had claimed to find evidence for prehistoric occupation of Sandia Cave (near Albuquerque), including bones of mastodons, and 'Sandia Points' which he estimated to be 25,000 years old - making the (discredited) 'Sandia Man' much older than any other culture of the southwestern USA. In 1943 Hibben visited Alaska, and 'discovered' mammoth bones and projectile points similar to the Folsom Points of New Mexico; a subsequent visit to the site by another group of investigators in 1978 did not find it to be as described by Hibben. Although Hibben maintained his claims, and insisted that he was innocent of misconduct, these 'discoveries' have been discredited.

With this in view, it seems that the Los Lunas Inscription may also be part of the Hibben legacy towards fake archaeology in New Mexico.

The Bat Creek Stone was found when the Smithsonian Institution carried out an excavation of Native American burial mounds in Tennessee in 1889. At the time the stone was discovered the excavation director, Cyrus Thomas, identified the inscription as being in the Cherokee writing system invented by Sequoyah - though he did not give a translation of the 'inscription'. Thomas was an entomologist, not an archaeologist or a linguist; he did not excavate the Mounds himself, but delegated the work to assistants, including John Emmert who excavated the Bat Creek Mounds.

The Bat Creek Stone was found when the Smithsonian Institution carried out an excavation of Native American burial mounds in Tennessee in 1889. At the time the stone was discovered the excavation director, Cyrus Thomas, identified the inscription as being in the Cherokee writing system invented by Sequoyah - though he did not give a translation of the 'inscription'. Thomas was an entomologist, not an archaeologist or a linguist; he did not excavate the Mounds himself, but delegated the work to assistants, including John Emmert who excavated the Bat Creek Mounds.

The Bat Creek inscription sat in storage for most of the next seventy years without being given much attention. In the 1960s one of the staff was doubtful that the inscription was in Cherokee, and sent a photo to Cyrus Gordon, a professor of Mediterranean Studies at Brandeis University. Gordon had a pet theory that there had been trans-Atlantic contact between early civilizations and pre-Columbian America - so he noticed a similarity to Paleo-Hebrew, and interpreted the five left-hand characters as being Paleo-Hebrew for "for the Jew(s)". Other archaeologists and epigraphers joined in the debate - some favoring Cherokee, some Paleo-Hebrew, although neither language was a perfect fit. The general conclusion was that Emmert had forged the inscription in order to impress Thomas and secure permanent employment at the Mounds. Another opinion is that Emmert was set up by a political opponent, in the hopes that he would be discredited and lose his job when the inscription proved to be a forgery.

One puzzling aspect, though, was the similarity to Paleo-Hebrew, particularly in that a word could be fitted to it. This was clarified in 2004, when Robert Mainfort and Mary Kwas found an illustration in a masonic reference book published in 1870 - it was an artist's impression of how the phrase "Holiness to the Lord" would be written in the Paleo-Hebrew script, and it contained a series of letters almost identical to those on the Bat Creek Stone. They concluded that the forger had used this illustration as the source for the forgery.

One puzzling aspect, though, was the similarity to Paleo-Hebrew, particularly in that a word could be fitted to it. This was clarified in 2004, when Robert Mainfort and Mary Kwas found an illustration in a masonic reference book published in 1870 - it was an artist's impression of how the phrase "Holiness to the Lord" would be written in the Paleo-Hebrew script, and it contained a series of letters almost identical to those on the Bat Creek Stone. They concluded that the forger had used this illustration as the source for the forgery.

The Smithsonian retains the Bat Creek Stone as part of its collection of archaeological frauds.

The Bar Kochba Coin from Clay City, Kentucky, was found in a pig-pen in 1952. Simon Bar Kochba led the Second Jewish Revolt in Israel in AD 122-135, and this coin was originally thought to have come from that time and place. It was eventually identified as a twentieth-century replica made for sale to tourists to the Holy Land. There are (unsubstantiated) reports of about three other 'Bar Kochba coins' found in Kentucky, South Carolina, and Missouri/Arkansas. One explanation for these findings might be that the coins were distributed honestly by a religious supply house as mementos of the Holy Land, were lost by their owners, and subsequently discovered by people who did not know that they were replicas rather than genuine first-century coins.

The Bar Kochba Coin from Clay City, Kentucky, was found in a pig-pen in 1952. Simon Bar Kochba led the Second Jewish Revolt in Israel in AD 122-135, and this coin was originally thought to have come from that time and place. It was eventually identified as a twentieth-century replica made for sale to tourists to the Holy Land. There are (unsubstantiated) reports of about three other 'Bar Kochba coins' found in Kentucky, South Carolina, and Missouri/Arkansas. One explanation for these findings might be that the coins were distributed honestly by a religious supply house as mementos of the Holy Land, were lost by their owners, and subsequently discovered by people who did not know that they were replicas rather than genuine first-century coins.

![]()

Unprovenanced Artefacts

Unprovenanced Artefacts

"Unprovenanced" means that we do not know where the artefact came from - there is no record of where it was found, what else was found with it, or who found it. Some unprovenanced articles are due to excavators or museums not keeping good records, but most are probably due to illegal digging and sale of articles to private collectors. It is much harder to date an unprovenanced find, as it cannot be related to the stratigraphic levels of a dig.

The James' Ossuary is a case in point - there seems to be no record of its existence before its present owner.

What appears to be a genuine article in this category is the ivory head of a scepter, carved to resemble a pomegranate, which was found in 1979 when Andre' Lemaire visited an antique shop in Jerusalem. The pomegranate also has an inscription in palaeo-hebrew scratched on it, identifying it as being for use in "the House of the Lord". No one knows where the pomegranate was found, or how the antiquities dealer acquired it. Lemaire was not able to buy the pomegranate, but he did manage to take photos of it. By the time the significance of the inscription was realized, the antiquities dealer had disappeared, and could not be located. In 1987, a tour guide named Meir Urbach offered the Israel Museum the pomegranate for $600,000. Meir Urbach claimed to know who actually owned the pomegranate. Amid all the intrigue and haggling, the Museum tried to raise the $600,000, but was not able to do so. In the meantime, the piece was smuggled to Paris and was exhibited at the Grand Palais. In 1988 an agent informed the Israel Museum that it would receive a gift of $675,000 to purchase the Pomegranate. Anonymous gifts such as this are not unheard of, but Museum officials usually know the donor. However, this was not the case here. No one knows who gave the money to the Museum. According to sources, the original antiquities dealer sold the pomegranate for $3,000. In view of its clouded history, and the differing verdicts of 'experts' there is no clear consensus as to whether or not the scepter head is a forgery or a genuine relic from the Temple of Solomon.

What appears to be a genuine article in this category is the ivory head of a scepter, carved to resemble a pomegranate, which was found in 1979 when Andre' Lemaire visited an antique shop in Jerusalem. The pomegranate also has an inscription in palaeo-hebrew scratched on it, identifying it as being for use in "the House of the Lord". No one knows where the pomegranate was found, or how the antiquities dealer acquired it. Lemaire was not able to buy the pomegranate, but he did manage to take photos of it. By the time the significance of the inscription was realized, the antiquities dealer had disappeared, and could not be located. In 1987, a tour guide named Meir Urbach offered the Israel Museum the pomegranate for $600,000. Meir Urbach claimed to know who actually owned the pomegranate. Amid all the intrigue and haggling, the Museum tried to raise the $600,000, but was not able to do so. In the meantime, the piece was smuggled to Paris and was exhibited at the Grand Palais. In 1988 an agent informed the Israel Museum that it would receive a gift of $675,000 to purchase the Pomegranate. Anonymous gifts such as this are not unheard of, but Museum officials usually know the donor. However, this was not the case here. No one knows who gave the money to the Museum. According to sources, the original antiquities dealer sold the pomegranate for $3,000. In view of its clouded history, and the differing verdicts of 'experts' there is no clear consensus as to whether or not the scepter head is a forgery or a genuine relic from the Temple of Solomon.

![]()

Private Collections

Private Collections

There is an ongoing discussion amongst archaeologists and collectors as to whether private collections are a good or a bad thing. The fact that someone is willing to pay large amounts of money for items for a collection is one of the main reasons for the trade in antiquities, and for illegal digs and the looting of archaeological sites. On the positive side, some collectors make their collections available for others to study, or even build museums to display their collection publicly. However, many private collectors keep their collections to themselves, do not publicize them, or make them available, and the artefacts 'disappear'.

![]()

Illegal Digs

Illegal Digs

Most countries now have strict regulations intended to protect their cultural heritage -

Most countries now have strict regulations intended to protect their cultural heritage -

one cannot just go and dig haphazardly anywhere one wants. Modern regulations usually require that any artefacts found remain in the country - in Israel archaeologists are allowed to keep artefacts for study until they have published a report of the dig, then the artefacts are put in a storehouse - they may be loaned to other countries to go on exhibition in public museums, but they remain the property of the State of Israel. Also, the leader of a legal licensed dig in Israel must publish the results of the dig within 10 years (though many drag their feet and take longer than this). In an illegal dig, there is no intention of studying the strata and carrying out a scientific examination of the finds, and certainly not of publishing the results - all that is intended is to find something to sell. So the whole of the Middle East is plagued by desperately poor people digging holes into ancient sites merely to look for anything that they might sell to the antiquities dealers or private collectors.

one cannot just go and dig haphazardly anywhere one wants. Modern regulations usually require that any artefacts found remain in the country - in Israel archaeologists are allowed to keep artefacts for study until they have published a report of the dig, then the artefacts are put in a storehouse - they may be loaned to other countries to go on exhibition in public museums, but they remain the property of the State of Israel. Also, the leader of a legal licensed dig in Israel must publish the results of the dig within 10 years (though many drag their feet and take longer than this). In an illegal dig, there is no intention of studying the strata and carrying out a scientific examination of the finds, and certainly not of publishing the results - all that is intended is to find something to sell. So the whole of the Middle East is plagued by desperately poor people digging holes into ancient sites merely to look for anything that they might sell to the antiquities dealers or private collectors.

![]()

Black Market

Black Market

Along with illegal digs, there is a black market in antiquities. Some antiquities dealers are prepared to sell the finds from illegal digs, and some collectors are prepared to pay high prices, and arrange to smuggle the objects out of their country of origin. The artefacts then disappear into a private collection, and their whereabouts is unknown to the rest of the world. This has happened to a number of objects, and is probably what has happened to some of the articles from the Iraq National Museum.

One instance involved the Dead Sea Scrolls - the first scrolls were found in 1947, by a Bedouin goatherd who took them to a dealer in Bethlehem. The dealer put them in a cardboard shoe-box and hid them under the floor of his house, during the war between Israel and the Arab nations, while he haggled with museums and collectors around the world to see how high he could drive the price. Meanwhile, the scrolls were deteriorating from the dampness of their hiding place. Eventually the Israeli government managed to out-bid their competitors, and bought the Scrolls.

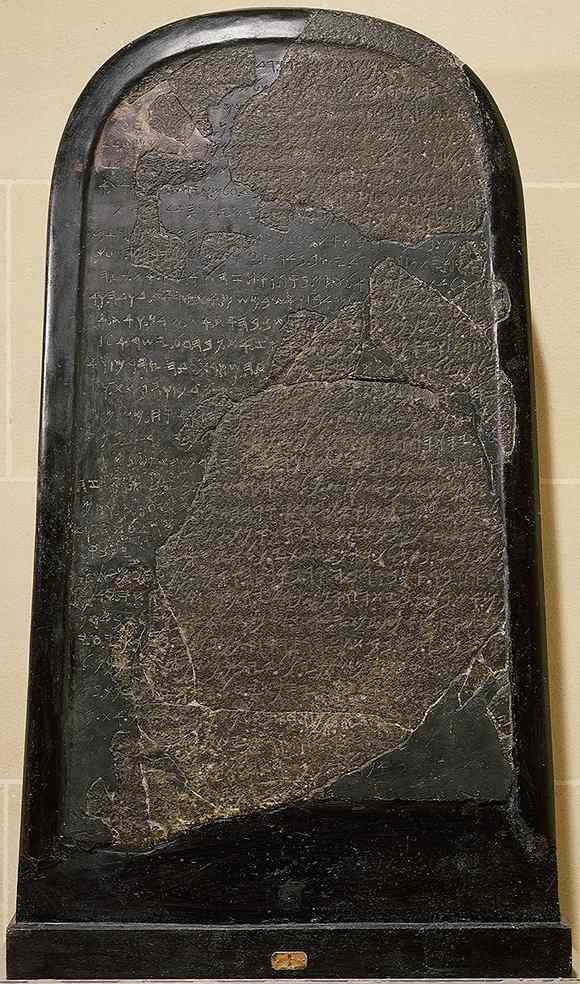

A second example is that of the "Moabite Stone", also called the "Mesha Stele" - a stele is an upright stone with an inscription or carving on it. The Moabite Stone has an inscription honoring Mesha, king of Moab. Moab was to the east of Israel; it was subjugated by King David, but rebelled during the reign of King Jehoram of the northern kingdom of Israel, and regained independence, with its own king, Mesha of Moab. The Moabite stone was found in 1868 by bedouin at Dibon, in what was then Transjordan (now the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan). A German pastor working for the French government was traveling in that region at the time, and was shown the stone - it was in one almost complete piece, and he was allowed to make a "squeeze" of the stone so that he could study the inscription. A squeeze is made by pressing a wet paper paste onto a stone, metal, or other object, then allowing it to dry, and peeling the dried layer carefully off the object.

Accounts as to what happened next vary from one source to another : either the bedouin decided to have a party and blew up the stone by accident, or else they thought that if they could break the stone up they would get more money by selling small pieces to various collectors - so they either blew it up with gunpowder, or they lit a fire on it and then poured water on it to crack it. The stone was indeed broken up, and in the process several pieces were lost. Then the remaining pieces were sold to different buyers. Eventually the Louvre Museum in Paris managed to assemble all the pieces that could be found, and rebuilt the stone, using the squeeze to reconstruct the missing pieces.

Accounts as to what happened next vary from one source to another : either the bedouin decided to have a party and blew up the stone by accident, or else they thought that if they could break the stone up they would get more money by selling small pieces to various collectors - so they either blew it up with gunpowder, or they lit a fire on it and then poured water on it to crack it. The stone was indeed broken up, and in the process several pieces were lost. Then the remaining pieces were sold to different buyers. Eventually the Louvre Museum in Paris managed to assemble all the pieces that could be found, and rebuilt the stone, using the squeeze to reconstruct the missing pieces.

![]()

Theft

Theft

Any object of great value is a temptation to thieves. In the case of archaeological objects, although they can be insured, there is no adequate compensation for the loss of part of the world's cultural heritage. Most museums have anti-theft devices installed, and guards near some of the most valuable objects, but there are thousands of objects kept in storage and not on public display. There have been cases of theft from museums and private collections, but they are often not made public. It would seem that some of the antiquities from the National Museum of Iraq may have been stolen by inside workers or sold illegally by Saddam Hussein even before the general looting of the Museum, to finance his building and military projects - the total loss from the Museum is not known with certainty.

![]()

Looting

Looting

I would define theft as the stealing of a particular article, or articles, which a thief premeditated and planned in advance. The article itself might be damaged in the process of the theft, but the other pieces of a collection might be left untouched. Looting, on the other hand, involves wholesale taking of anything of apparent value, and often the destruction of whatever else remains. The looters are often soldiers, in the case of a war, or local people who steal from nearby archaeological sites, which usually cannot be guarded adequately. Whatever is stolen is often damaged because those involved do not know how to take care of antiquities, and are in a hurry to get to the illegal dealers.

I would define theft as the stealing of a particular article, or articles, which a thief premeditated and planned in advance. The article itself might be damaged in the process of the theft, but the other pieces of a collection might be left untouched. Looting, on the other hand, involves wholesale taking of anything of apparent value, and often the destruction of whatever else remains. The looters are often soldiers, in the case of a war, or local people who steal from nearby archaeological sites, which usually cannot be guarded adequately. Whatever is stolen is often damaged because those involved do not know how to take care of antiquities, and are in a hurry to get to the illegal dealers.

Widespread looting has been taking place for years in Afghanistan, and in Iraq even before the fall of the Saddam Hussein regime

![]()

War

War

In a war between nations, the aim is to win the war, regardless of the cost. Museums, and also some archaeological sites, are usually located in the capital city of a nation, and so are likely to be damaged or destroyed during a war. Civilized nations will try to avoid damage to our world-wide cultural heritage - in WW II the allies agreed not to bomb the German city of Heidelberg because of its history and culture. The treasures from the British Museum, located in London, were removed and stored in safer places in Britain.

Though the museums in Berlin survived WW II, some of the treasures from the Pergamom Museum, which was in the Russian sector of Berlin after the war, 'disappeared'. These included 'the Treasure of Priam' (the gold hoard discovered by Heinrich and Sophia Schliemann at Troy). It was rumored that Russian soldiers had taken it, but the Soviets initially disclaimed all knowledge of the treasure until recently. At last it was revealed that the treasure had surface in Russia, and is now in a museum there - the Russians refuse to return it to Germany, on the grounds that Germany owes reparation to Russia for damage done during WW II.

In the case of the war in Iraq, measures were supposed to be taken to safeguard the treasures of the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad - but that presupposed the co-operation of the museum staff, who were intimidated by the Saddam Hussein regime

Go here for a description of the tragedy of the antiquities of Iraq

![]()

Political and Ethnic problems

Political and Ethnic problems

In some of the regions of the Middle East and the Mediterranean the population is not homogeneous but is composed of groups with different ethnic or religious backgrounds. What is important to one group may not be of importance to the other, and may be targeted for destruction as being associated with the "other" group. Archaeological remains are often such targets.

During the Turkish regime in Greece, the Turks used the Parthenon in Athens for shelling practice.

In Afghanistan, the Moslem regime decided to destroy Buddhist sites, and blew up statues which were centuries old.

In Israel/Palestine, and in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Jewish and Christian remains have been destroyed or mutilated by Muslim Arabs - "Joseph's Tomb" was destroyed by an Arab mob, the face of David was gouged out of a mosaic on the floor of a synagogue in Gaza, and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem was used as a refuge by Palestinian gunmen and eventually set on fire - and then allowed by the Israelis to burn for several days. Of particular concern is the ongoing unsupervised excavation under the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and the dumping of excavated dirt, containing archaeological remains, by the Muslim authorities who claim to be extending an underground mosque, and making an emergency exit for the mosque. Because of the religious sensitivities in regard to the Temple Mount, and probably for the sake of peace and quiet, the Israeli authorities are not enforcing the usual regulations for supervising excavation and licensing the digging.

![]()

Removal of Cultural Heritage

Removal of Cultural Heritage

In the early days of archaeology, when the emphasis was more that of a treasure hunt than on learning about how people had lived in earlier times, archaeologists usually sent their finds back to their own country, either for themselves, or for a Museum in that country. This was also one of the main ways of financing a dig in those times. There are good and bad sides to this. In some cases the finds were preserved and made available for study by anyone in the world, rather than being left in remote and inaccessible places where they were endangered and uncared for. On the other hand, the cultural heritage of a people, and their national identity, is affected by the remains of their ancestors, and there is a growing movement nowadays to return some of these treasures to their country or place of origin. As an example, the bones of ancient Native Americans are being returned for burial in their traditional burial grounds rather then being kept in museums.

Items of ongoing international debate and dispute are the Elgin Marbles, taken by Lord Elgin from the Parthenon in Athens and later sold to the British Museum (he did save them from destruction by the Turks); the Rosetta Stone, taken by Napoleon from Egypt, then captured by the British, and presently in the British Museum with a modern copy in the Cairo Museum; and the Siloam Inscription - during the Turkish regime in Jerusalem this inscription was secretly chiseled out of the wall of Hezekiah's Water Tunnel and smuggled to Turkey, where it is still kept.

There are, however, some problems - because of population changes and the movement of nations, a land that "belongs" to one people now may have antiquities which are of more cultural importance to another group. For example, the Dead Sea Scrolls, which were written in Hebrew by Jewish Essenes living near the Dead Sea, are now claimed by the Palestinians who have been ceded the region where the Scrolls were found.

![]()

Economic Problems

Economic Problems

Many nations are faced with economic problems which it seems cannot be resolved without the destruction of ancient remains.

Egypt needed to control the flooding of the Nile, and have a safe water supply. The answer to this was to build a dam at Aswan - but the waters of the dam would cover the temples which Ramesses II had built at Abu Simbel, and which are a World Cultural Heritage Site.

Similarly, Turkey and Iraq are both constructing dams which will inundate important archaeological sites.

In many cities with a long cultural history, people are still living on top of the archaeological remains from centuries of the past - Jerusalem, Mexico City, Rome, Athens, London, are all built over previous layers of occupation. One cannot dig the foundations for a new building, or make a parking lot, or put in sewers, without digging into archaeological remains.

A partial answer to this is to mount a "Rescue Dig" or "Salvage Dig" - archaeologists do as much work as they can before the bulldozers move in, and photograph and/or remove artefacts before they are destroyed. In the case of the Aswan dam, an international team cut the statues and temples of Abu Simbel into pieces, and re-assembled the whole complex above the water level.

As another example, in one of the hotels in Athens, the foundations of the hotel uncovered the city wall from the time of the Persian Wars - the building was modified, so now one goes to the dining room of the hotel, in the basement, and walks past glass display windows which look out at the excavated underground portions of the wall.

In the case of Jerusalem, the modern dwelling-houses near the Temple Mount and parts of the Ophel were cleared away, to allow ongoing archaeological excavation and the construction of an archaeological park. This contributed to the tension between Arabs and Israelis because it caused hardship to the Arab inhabitants of the houses, who had lived there for generations.

![]()

Damage by Tourists and Nut Cases

Damage by Tourists and Nut Cases

Archaeological sites are generally fragile - although they may look to be "just piles of stones" they can start to disintegrate or be destroyed by people walking over them. In the case of caves or enclosed spaces, the moisture in the air caused by numbers of people breathing can cause fibres to rot, and paintings to start peeling off walls. A further problem is that tourists often "pick up" what they regard as a little insignificant piece of something from a site, and take it home with them - and in so doing remove a valuable piece of evidence from the site. As one example, a tourist took a small tablet from a site, and only after he had had it for several years did he notice that there was some writing on it. On further examination by experts, the writing was deciphered, and gave the name of the city where it was found, which up until then had not been known with certainty.

Most such damage is done inadvertently and in ignorance. However, there are some instances of deranged people who, for no apparent reason, attack and smash an article on display in a museum - the Portland Vase was a (probable) Roman vase on display in the British Museum. In 1845 someone took an axe and smashed it, or else stumbled in a drunken stupor and fell against it - accounts vary. It has been re-assembled and pieced together again.

![]()

Academic jealousy and personal antagonism between archaeologists

Academic jealousy and personal antagonism between archaeologists

It would be nice if archaeologists all got along together, and co-operated with one another, and for the most part they do. However, as in Portales, there are "3 or 4 Old Grouches". The work on the Dead Sea Scrolls brought out personal feuds, accusations, even law cases, as one of the scholars claimed that he had prior rights to translation, and would not let others see "his" scroll fragments - not even to show them a photograph. The whole mess dragged on for years, and the work of translating the scrolls was greatly delayed by the in-fighting and personal rivalry that went on.

Reading about them is unedifying

Copyright © 1999 Shirley J. Rollinson, all Rights Reserved